1.

Dreieckbild (Triangle Picture)

Acrylic behind glass, artist frame (wood)

38 x 48 cm

1995

2.

Zigarrenbanderolenbild (Cigar Bands Picture)

Acrylic behind glass, artist frame (wood)

51 x 81 cm

1989

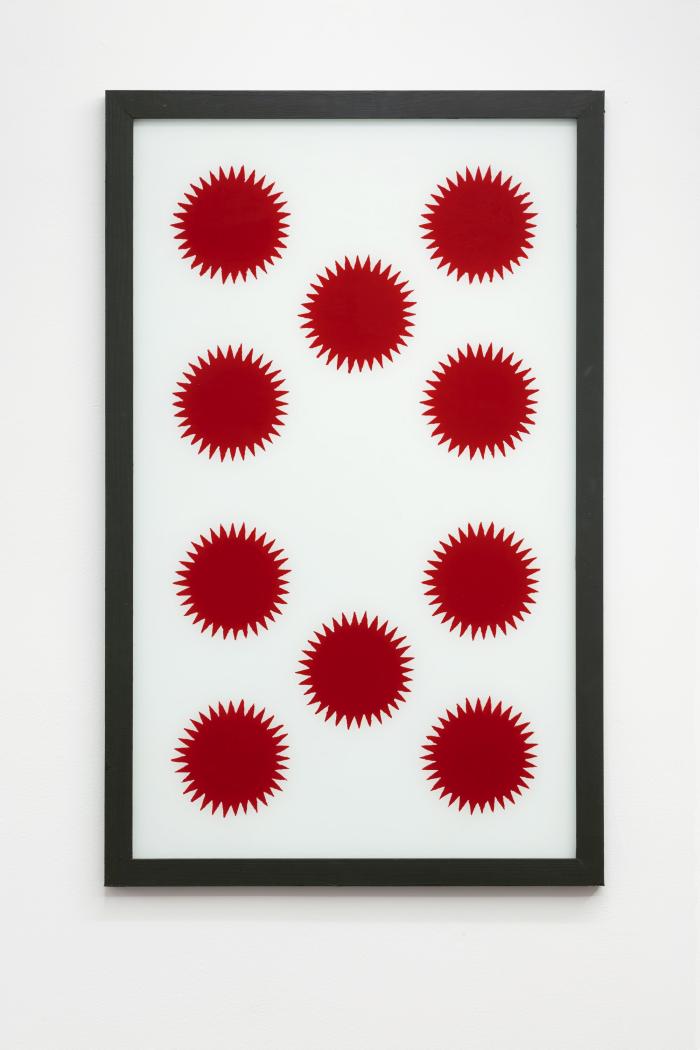

3.

10 Rote Sonnen

Acrylic behind glass, artist frame (wood)

51 x 81 cm

1989

4.

Marienkäferbild (Ladybug Picture)

Acrylic behind glass, artist frame (wood)

30 x 40 cm

1986 / 2023

5.

4 Felder (4 Fields)

Acrylic behind glass, artist frame (wood)

51 x 81 cm

1990

6.

ZIB

Looped film

52 Seconds

2008

7.

Kleines Karobild (Check Picture)

Acrylic behind glass, artist frame (wood)

38 x 48 cm

1994

8.

Lebkuchenbild (Gingerbread Picture)

Acrylic behind glass, artist frame (wood)

156 x 96 cm

1988

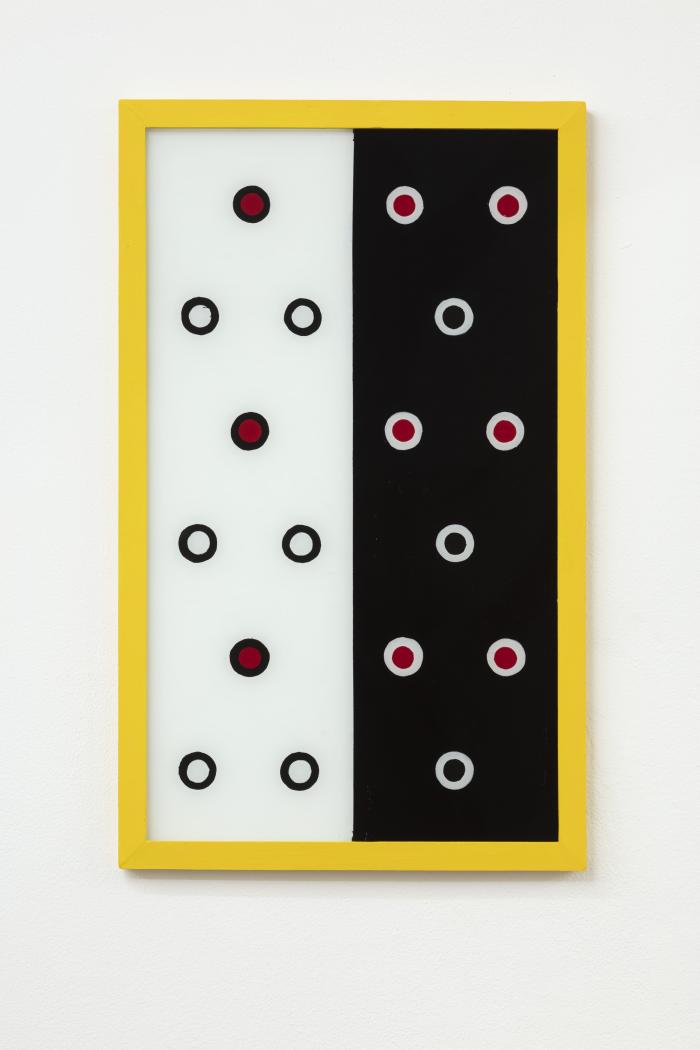

9.

Halbschwarzes Bild (Half Black Picture)

Acrylic behind glass, artist frame (wood)

33 x 54 cm

1989 / 2023

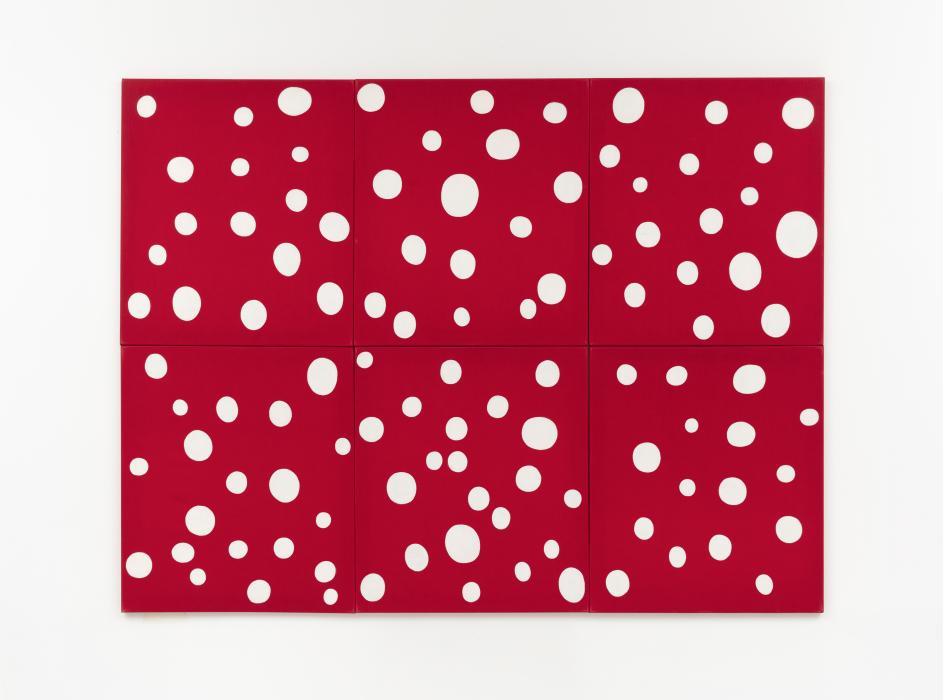

1.

Punktebild (Dots Picture)

Fabric paint on coloured cotton batiste, wooden stretcher, 6 parts

210 x 160 cm

1986

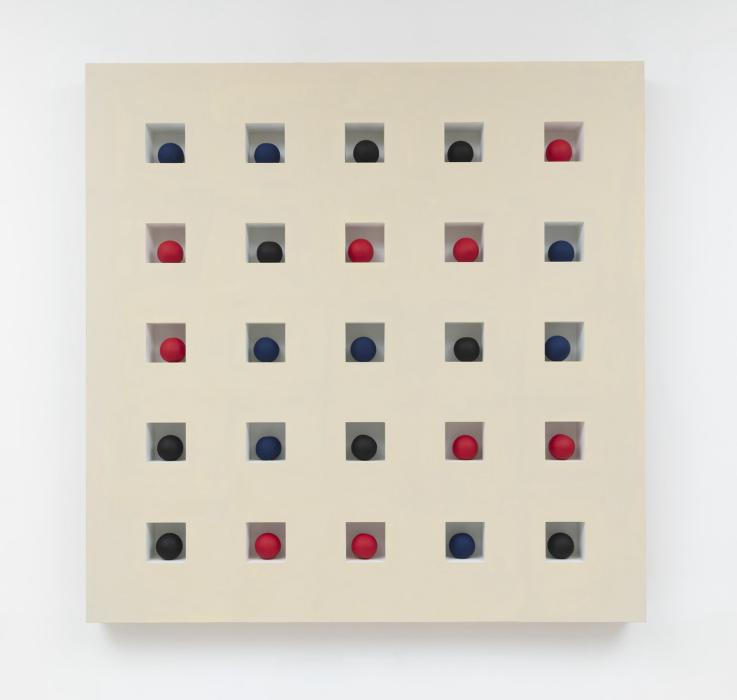

2.

Nischenbild (Niche Picture)

Acrylic on wood, plaster

170 x 170 x 12 cm

1987 / 2023

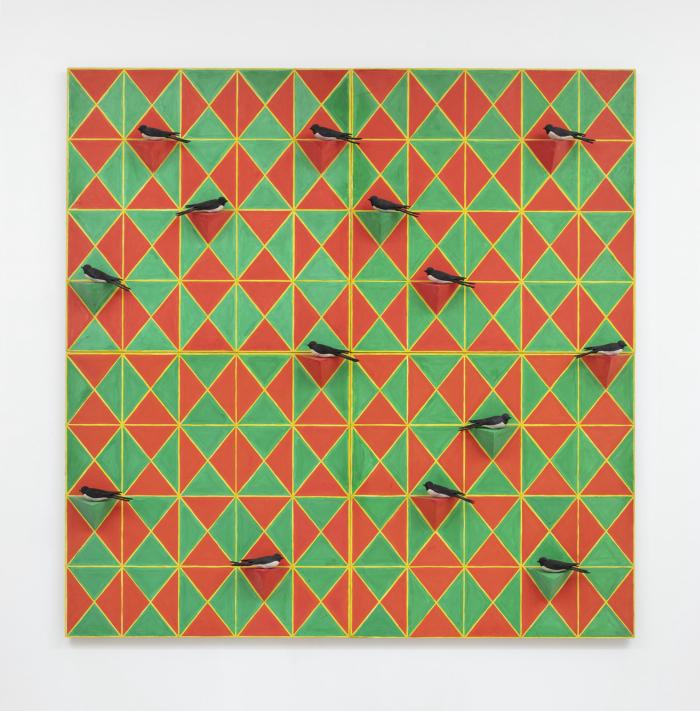

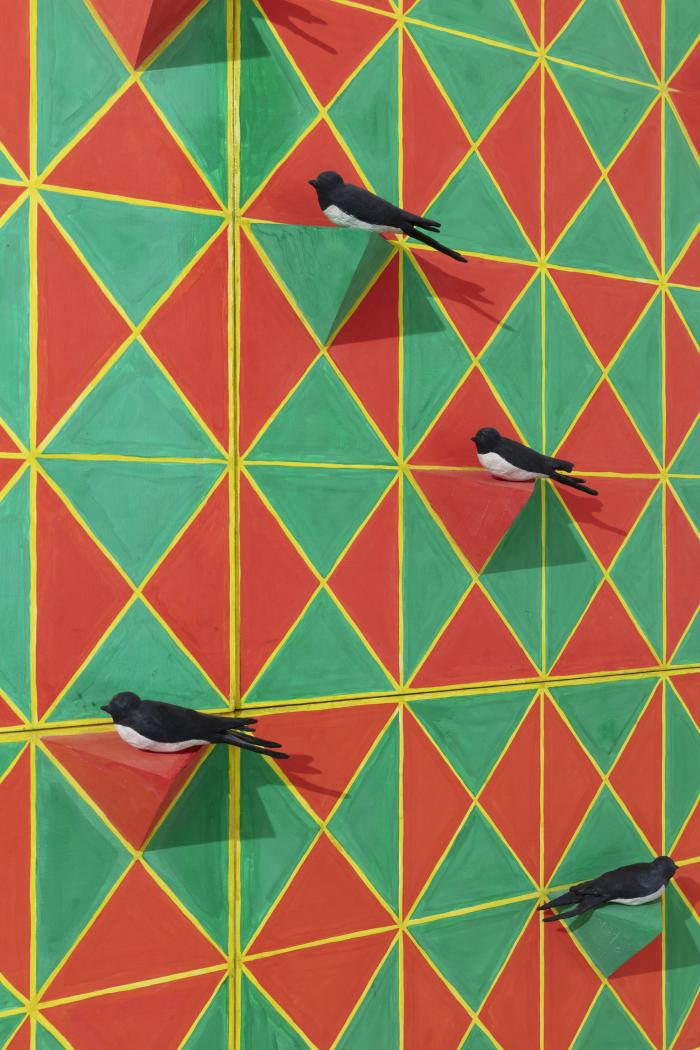

3.

Schwalbenbild (Swallow Picture)

Gouache on wood, plaster, 4 parts

170 x 170 x 15 cm

1986

4.

Pinguinbild (Penguin Picture)

Fabric paint on coloured cotton batiste, wooden stretcher, 4 parts

178 x 198 cm

1987

5.

Noppenwürfel (Dimple Cube)

Acrylic on wood

32.5 x 32.5 x 32.5 cm

1987

Elke Denda’s exhibition at Josey, titled ‘Projection’, gathers works made over a period of 22 years, from 1986 to 2008. Installed across two spaces, Willow Lane and Ten Bell Lane, the exhibition includes panel paintings, reliefs, floor sculpture, reverse glass paintings, and a video work. The relief Nischenbild (1987) and reverse glass paintings Marienkäferbild (1986) and Halbschwarzes Bild (1989) have been specially reconstructed for this occasion – the first time Denda has made work since quitting art in 2008. Denda’s last exhibition in 2008, featuring the video work ZIB (2008), shown at Willow Lane, was also the last for her Cologne gallery, Galerie Johnen + Schöttle.1

ZIB is a 52 seconds ‘supercut’ that fixatedly tracks spherical forms as they appear in disparate appropriated clips from television and cinema. The spheres as focus for, and symbol of, a restless gaze disrupts intended pictorial hierarchies of subject and object, foreground and background. Everything that is not the sphere becomes a background to be montaged into a world of endless audio-visual-spatial boundaries, limited, nonetheless, by the frame.

Installed alongside ZIB at Willow Lane are Denda’s reverse glass paintings. A folk technique made popular in the nineteenth century, used to paint devotional imagery, motifs applied in reverse with acrylic paint intensifies the colour when viewed through the frontal glass surface. At Josey the selected works span a period of nine years, but, in total, Denda produced these continuously for nearly two decades, beginning in 1986. Such a complete combination has not previously been exhibited.

Five works are installed at Ten Bell Lane. The paintings Punktebild (1986) and Pinguinbild (1987) each consist of panels that might, it seems, be added to or subtracted from. Thinly painted on light cotton fabric, Pinguinbild, showing penguins tesselated with circles and oblongs, displays its support as part of the pictorial composition. Schwalbenbild (1986) extends the planar pictorial surface into three dimensions: an array of simple cast swallows perch on diamond ledges extruded from a commedia dell'arte harlequin pattern ground. Nischenbild is gridded with geometric recesses housing miniature cast spheres handpainted in blue, red and black. Facing it on the floor, as if freed and transformed from the Nischenbild, is Noppenwürfel (1987). This searing volumetric object combines a language and form developed between these works in an intensely productive period of painterly inquiry for Denda.

Viewed as reproductions, squinting, or at a distance, Denda’s works appear to share a hard, inhuman manufactured edge, produced in collaboration with machines. Looking more closely, however, slickness breaks into a wholly more bodily facture: in the paintings uneven blooms of colour are subtended by loose underdrawings coming out at the sides – ‘subtle eccentricities’, as one commentator put it.2 The lines of the reverse glass paintings bubble and fizz, their painted wooden surrounds not frames but part of the picture. Painterly application oscillates between manufacture and facture – between machine and human hand – the personal and impersonal – the physical and the embodied – in a way that is deeply affecting. Denda has an extraordinary ability to conjure a certain irreducibly human emotionality in a commodity language of graphic reproduction.

Abstract elements in Denda’s pictures are typically anchored in actuality. Familiar images, selected for their personal resonance, become symbols that constitute, as she puts it, ‘an alphabet of the important elements of life’.3 Stripping back is, for Denda, a device to work towards abstraction rather than being abstraction itself. In the reverse glass paintings the imagery might be excerpted and transformed from some thing in the world, for example a ladybird. For Denda, the works must function as pictures on their own terms while simultaneously suggesting the possibility of endlessness, as if the motifs presented are just excerpts held by the frame that reach far beyond.

A viewer with an interpretive frame informed by modern abstract art will not be equipped for the language that Denda’s works demand. Stripped back and simplified, the non-specificity of the images teases at recognition that never quite arrives at its referent. Looking at the work on display at Josey their literalism is striking: a series of disarming disclosures. Everything that is the matter is present. Some, such as 4 Felder (1990) or Dreieckbild (1995), seem even hyper-prescriptive, as if answering more questions than they ask. The amplification of stylisation and rigid formality has the effect of hardening the work into ornamentation, seemingly deflecting any further interpretation. Yet, paradoxically, it’s actually at this apex where they become imbued with the thing they seem to be conscious of deflecting.

Writing about Denda’s work in 1988, the art historian Julian Heynen noted the ‘oscillation of decorative form and symbol’ which, he goes on, is ‘nowhere ironic or polemic against itself’.4 Heynen finds it necessary to defend Denda’s work against charges of irony, naivety and the ‘problem’ of decoration. In the meantime, forty years later, it is no longer necessary to defend against such things. Characterised by a refreshing total absence of irony, Denda’s technically uncomplicated take on abstraction is staggering in its simplicity and complexity.

~ Josey

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

1. Denda began showing with Galerie Johnen + Schöttle in 1985 while still a student of Fritz Schwegler at the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie. Schwegler exhibited at Norwich Gallery in 1996, invited by curator Lynda Morris.

2. See the catalogue for Humpty Dumpty’s Kaleidoscope: A New Generation of German Artists, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 1992.

3. Elke Denda in conversation with Josey, May 2023.

4. See catalogue for Bilder: Elke Denda, Thomas Ruff, Michael van Ofen, Krefeld/Haus Esters, 1988.

Elke Denda lives in Düsseldorf and studied at the Kunstakademie under professor Fritz Schwegler. Selected solo and group exhibitions include; ‘We are stardust, we are golden. Women at Johnen + Schöttle since 1984’, Galerie Johnen + Schöttle, Köln (2008); Galerie Lindig in Paludetto, Nürnberg (2002); Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg (1997); ‘Humpty-Dumpty's Kaleidoskop: A New Generation of German Artists’, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney (1992); ‘Anni Novanta’, Galleria Comunale di Arte Moderna, Bologna (1991); Galerie de Lege Ruimte, Brügge (1990); Museum Schloß Hardenberg, Velbert (1988); Museum Haus Esters, Krefeld (1988); Galerie Johnen & Schöttle, Köln (1985); Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, München (1984)