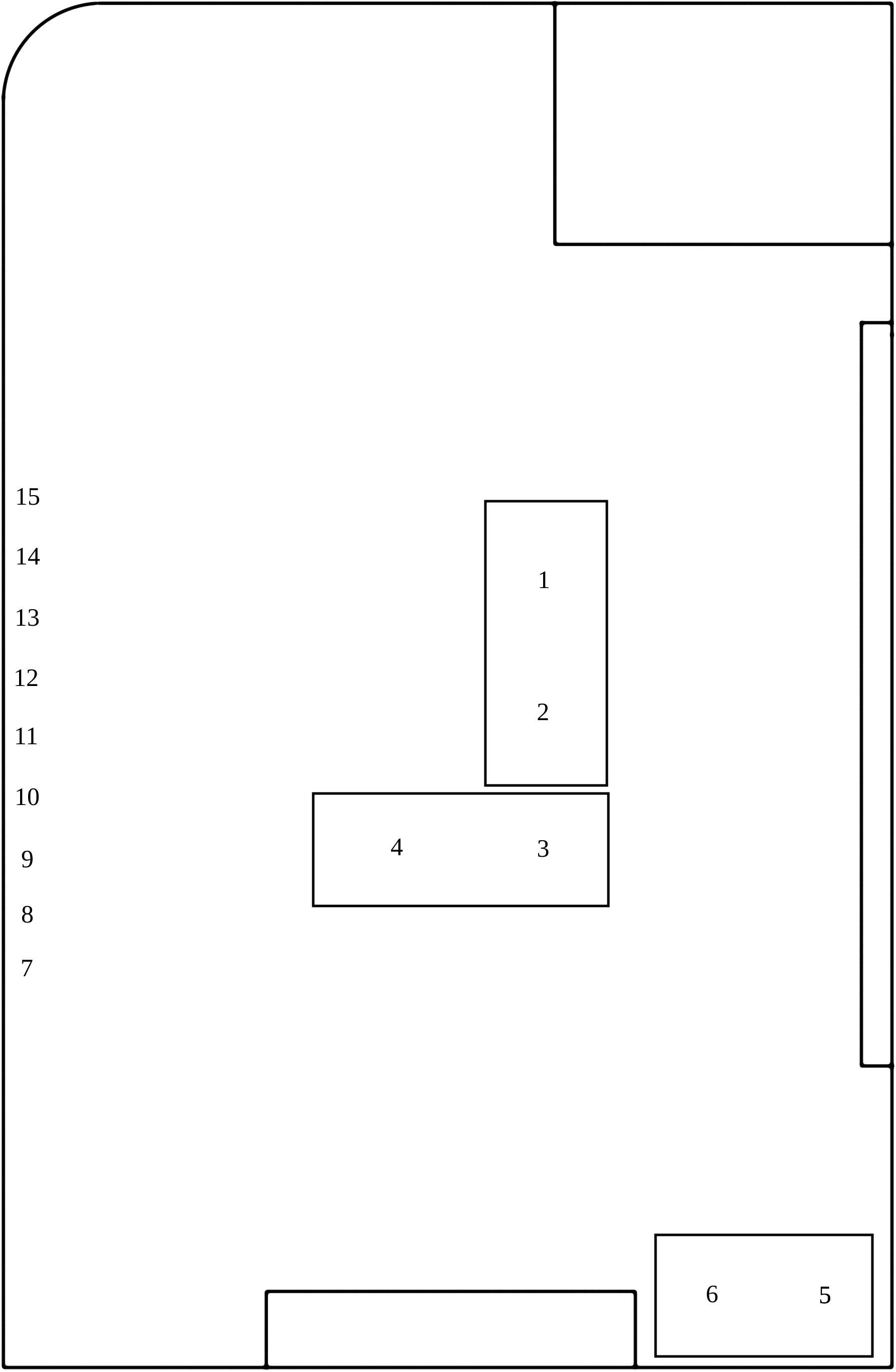

1.Lingam Ghosts and Universes

Stoneware with underglaze

23 x 13 cm

2023

2.Lingam

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

22 x 12.5 cm

2022

3.Lingam Fascinator

Stoneware with underglaze, glaze and lustre

23 x 13 cm

2023

4.Lingam for Agnes Martin

Stoneware with underglaze

19.5 x 13.5 cm

2022

5.Rocking Lingam

Stoneware with underglaze

22 x 26.5 cm

2023

6.Lingam

Stoneware with underglaze

20.5 x 12.5 cm

2023

7.Vase

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

9.5 x 9 cm

2021

8.Vase

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

10 x 9 cm

2021

9.Vase

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

12 x 10 cm

2020

10.Vase

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

12 x 9.5 cm

2023

11.Vase

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

10 x 9.5 cm

2021

12.Vase

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

11.5 x 10.5 cm

2023

13.Vase

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

11.5 x 10.5 cm

2020

14.Vase

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

12 x 9.5 cm

2019

15.Vase

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

11 x 9 cm

2021

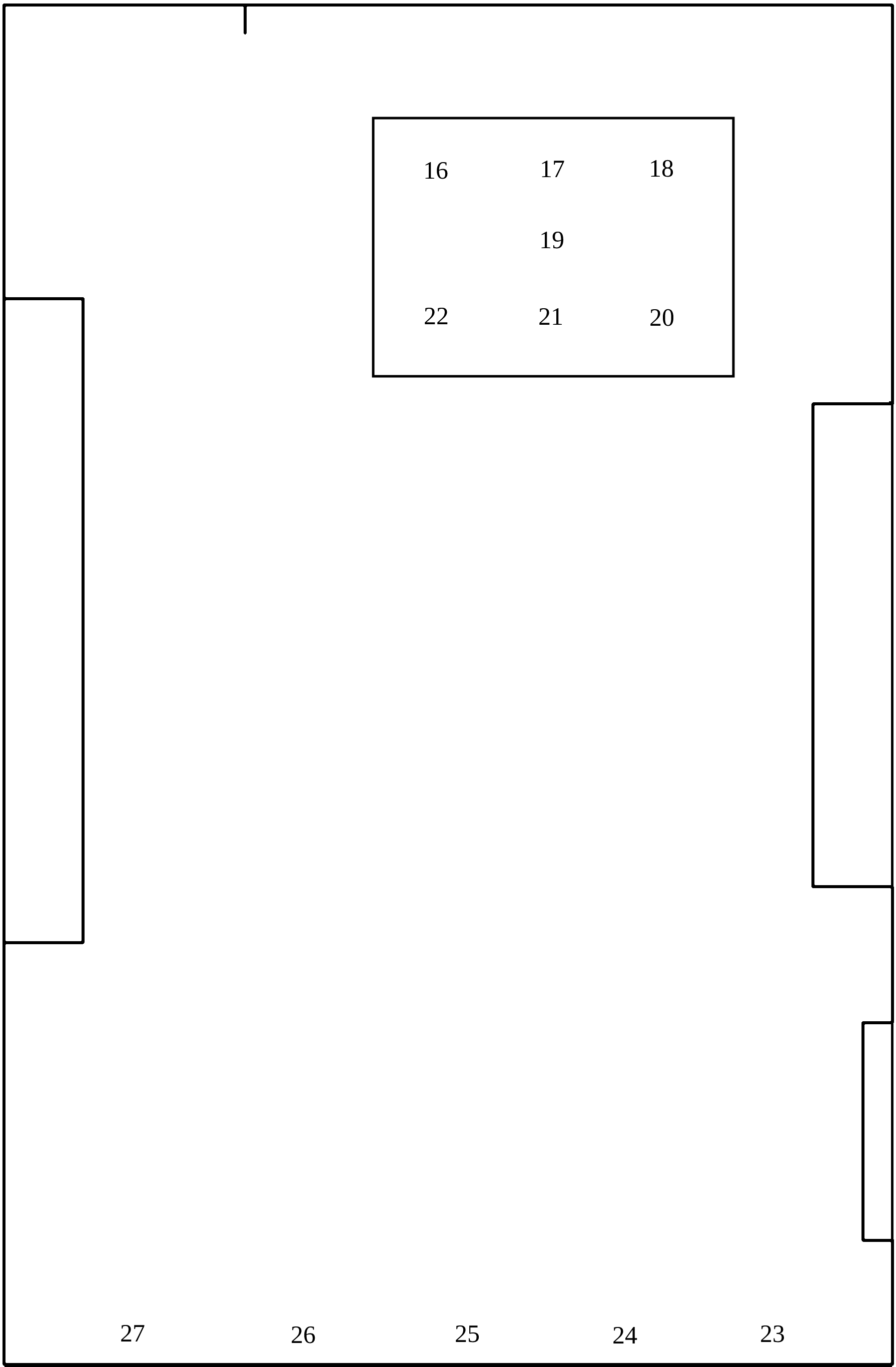

16.Make-It-Stop Rattle (Janet)

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

8 x 10.5 cm

2018

17.Lingam

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

5.5 x 8.5 cm

2016

18.Ghosts and Universes Rattle

Stoneware with underglaze

8.5 x 11.5 cm

2023

19.Ghosts and Universes Rattle

Stoneware with underglaze

10.5 x 12 cm

2023

20.Make-It-Stop Rattle (Xavi)

Stoneware with underglaze

11.5 x 14 cm

2023

21.Ghosts and Universes Rattle

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

7.5 x 10.5 cm

2016

22.Make-It-Stop Rattle (Bob)

Stoneware with underglaze

10 x 12.5 cm

2023

23.Genie Bottle

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

26 x 14 cm

2019

24.Genie Bottle

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

14 x 13 x 9.5 cm

2019

25.Genie Bottle (Roger)

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

18 x 12.5 cm

2023

26.Genie Bottle (Xavi)

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

17 x 14 cm

2020

27.Genie Bottle (Emily)

Stoneware with underglaze and glaze

18 x 13 cm

2023

I began studying ceramics at the College of Art in Edinburgh in 1966 and continued at UCLA, Berkeley, and San Francisco State University, and then at Ruby’s, a private studio in San Francisco. When I lived in Edinburgh, I traveled around England and northern Europe, looking at late medieval art and ceramics, my first steps on a path that led to my novel, Margery Kempe, about a woman who lived in East Anglia in the 15th Century. I stopped working with clay around 1975—earning a living, writing, and raising a child left no time. Instead, I collected ceramics from two obscure early 20th century Bay Area potteries, California Faience and Jalan. In 2015, I moved to Sweden with my husband and took up ceramics again. I love the Scandinavian potters—especially Gertrud Vasegaard, the Agnes Martin of clay. When we returned to San Francisco in 2017, I joined Ruby’s again. I prefer seeing myself as a student of clay, just to say.

Ceramics begins with the mystery of spinning mud. Spinning electron, spinning earth, spinning universe. My pots display the spin that brought them into existence. Somewhere Joseph Conrad observed that he thought of Nostromo as spherical. That was good news. My novels end with an image of spinning, and I also see them as spherical. When I write I feel as though I’m attaching scraps to a sphere, and if the story moves forward, it’s an effect of putting one thing next to another.

Making a bowl, a hollow form, is the creation or the acknowledgement of emptiness. Most of the objects in this show assert this emptiness—they are closed forms without access to the inside: rattles, genie bottles, and lingams. I want emptiness in writing as well, I want emptiness to travel along with the story. I tell myself that clay takes me in directions I don’t allow myself in writing, more sacred (for lack of a better word), but they may not be so different. I’ve fashioned quite a few urns and containers for people’s ashes—is there a better thing to do?

I often make a chaotic ground with an orderly pattern on top. I confect this ground in a rather complicated process, with brush, underglaze, sponge, and sandpaper. It’s like the poetry of my first hero, John Keats, an enameled surface over a welter of feeling. I am moved by the smooth surface and the chaos of feeling below. This may not be an exact description of each work, but more a feeling I have about words and clay.

If writing can be empty, clay can be full of story. Shapes and patters travel through history. Slowly covering a simple form with a geometric pattern connects me to history’s good side, as does, say, pouring tea. Think of Acoma ollas, think of fields of iznik tile, infinitely repeating, a culture goofing on eternity. Or the simple geometry that Gertrud Vasegaard patiently applied to her forms. I see this as a noble activity, like choosing one word over another, but why is that? Their beauty partly derives from their imperfections. Vasegaard struggles toward perfection and her mistakes are there for us to consider. The closer to perfection, the more evident the imperfections. We enjoy them as we do the spontaneities of a Japanese cup. The sheer aptness of her decoration unites with the form, and that somehow gives us a kind of consolation, that meaning exists in the world.

Sometimes my writing and my pots share a dark humor. Dark humor, obsessive subject matter and practice. Faces on the Make-It-Stop rattles contort with exasperation and terror, but it’s no use covering the ears because the noise comes from inside. Usually, they are faces of friends, or self-portraits. The Ghosts-and-Universes rattles are droll memento moris, the rows of squiggle-ghosts barely exist. Nonsense is the language of the dead. If I were a shaman this would be my rattle. The faces on the genie bottles often resemble my husband’s, for some reason.

Of course, I think about death. I’m seventy-six. I could live fifteen years, or I could die tomorrow. Neither would transgress the statistics. The thought of my death enthralls me! And seems narcissistic to dwell on? But that is modern thinking—in the past, I would be encouraged to think about nothing but, with idea that I would become more spiritual. But the odd thing is, I am becoming more spiritual, in my fashion.

Lingams are phallic shapes that are worshipped. They are emblems of creativity at every level, including its destructive power. If you go back far enough, you find such votaries in most cultures—like the veiled phallus in the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii, or the gold phalli of the Philistines. Even the Israelites put up phallic stones, and they carried--according to admittedly sketchy scholarship--a stone phallus in the Arc of the Covenant. Google it! Lingams certainly don’t mean the same thing in their cultures—they are habitations of deity, good luck amulets, fertility gods, markers indicating formlessness, signifiers that anchor the chain of signification. But this just begins the discussion, because the tension between masculine-feminine pervades all situations in my queer community, including collapsing these binaries of course. When I drape a phallus in a fascinator, a veil worn by women at rituals like weddings and funerals, I enter this conversation.

~ Robert Glück

Glück has exhibited his ceramics infrequently, most recently at the NCECA (National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts) conference in 2022. He is the author of two story collections, Elements and Denny Smith, and three novels, Jack the Modernist, Margery Kempe, and About Ed, which will be published by NYRB in 2023. His collected essays, Communal Nude, was published by Semiotex(e) in 2016. His books of poetry include Reader, La Fontaine with Bruce Boone, In Commemoration of the Visit with Kathleen Fraser, and I, Boombox, published by Roof Books in 2023. In the late 70’s, Glück and Bruce Boone founded New Narrative, a literary movement of self-reflexive storytelling that combines essay, lyric, and autobiography in one work. Glück served as director of The Poetry Center at San Francisco State University. He was co-director of Small Press Traffic Literary Center and associate editor at Lapis Press. He lives “high on a hill” in San Francisco.