1.

Blow Up Ad Man with Gold Medallion

Acrylic on paper

84 x 68 cm

1981

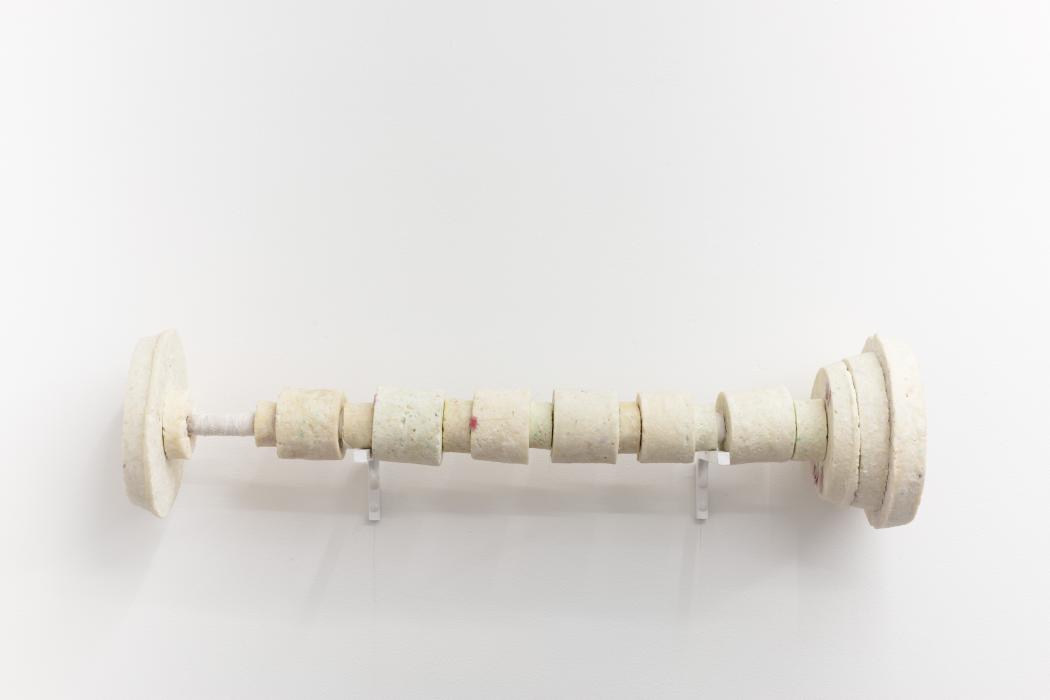

2.

Plato. Indochina creamware

GWASH Cast washing powder and glue with photocopies and photographs with

The Allies commemorative plate

20 x 220 cm

1992

3.

Coffee Table

Mixed media

103 x 125 x 35cm

2003

4.

Homo

Mixed media lightbox

25 x 50 x 7 cm

1991

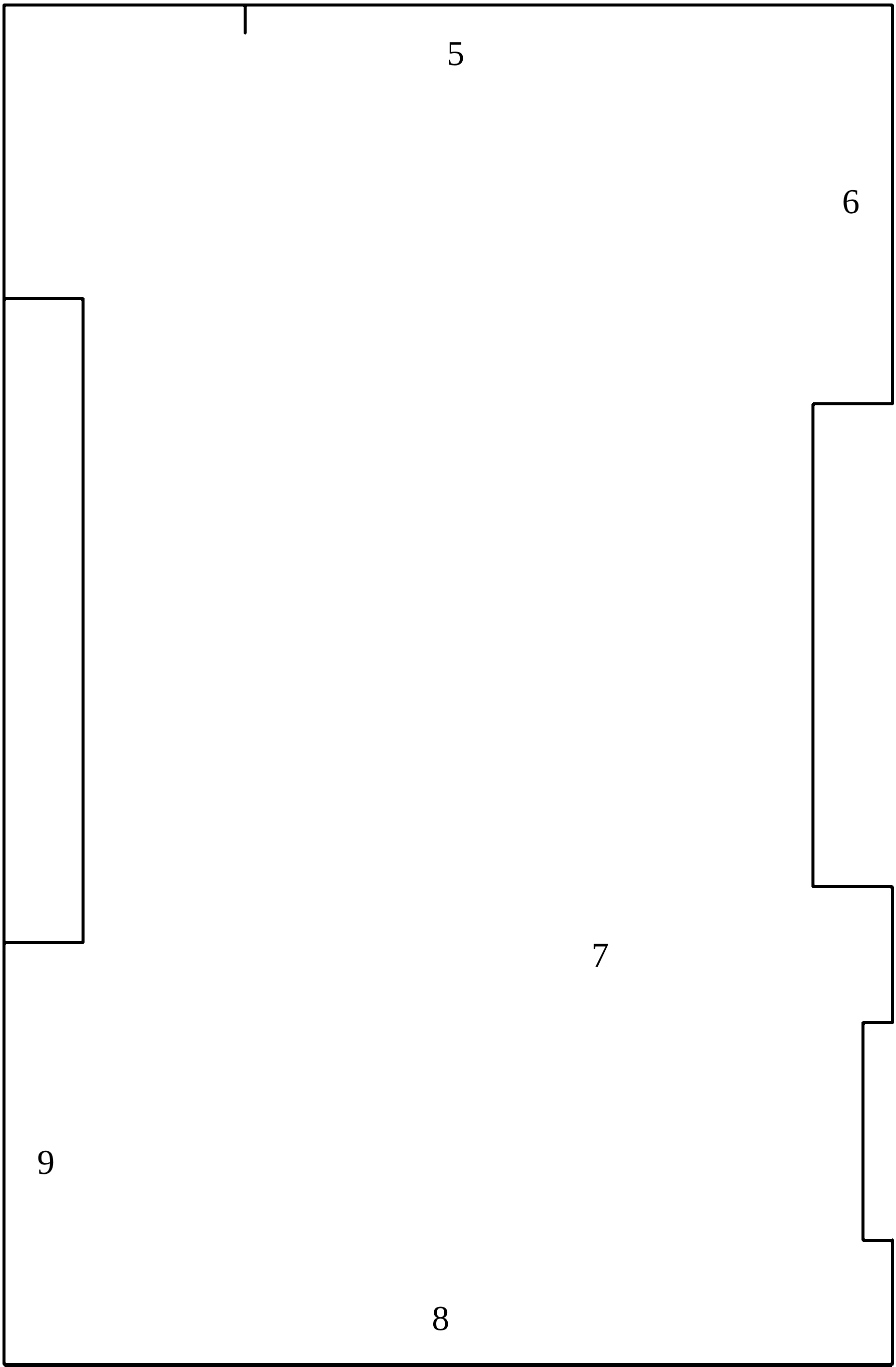

5.

Decorative Stump 1

GWASH Cast washing powder and glue, wood

25 x 80 cm

2003

6.

Back (bat) To the Future with Poppies on Edgehill

Oil on canvas

51 x 105 cm

2022

7.

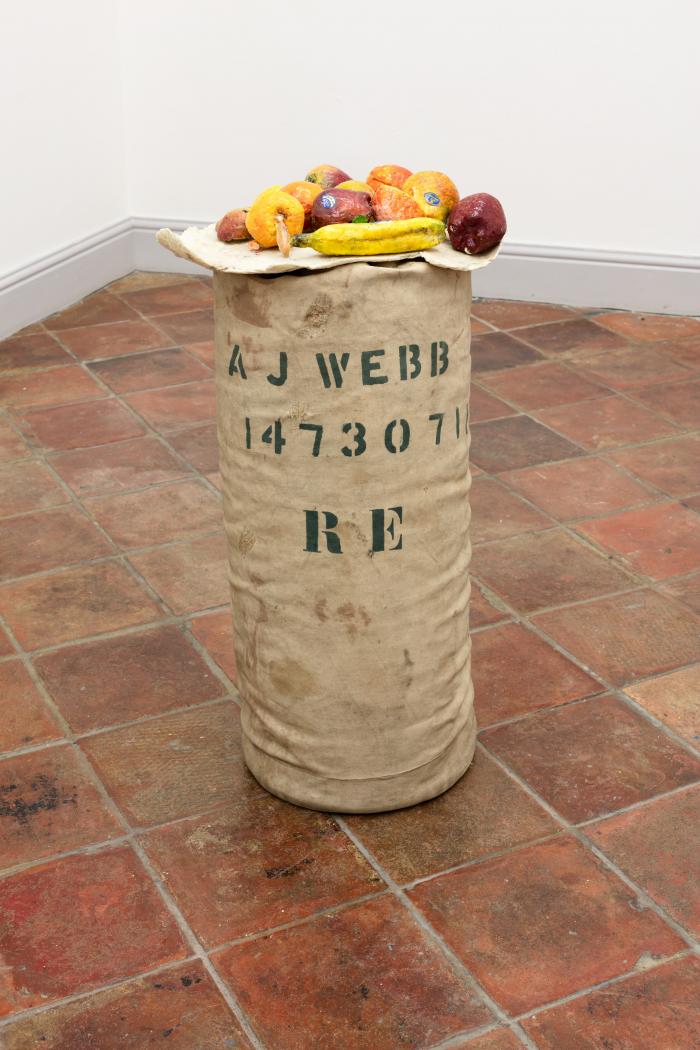

Fruit Plate on Kit Bag

Mixed media

68 x 45 cm

1981

8.

Addicted to Poppies

Oil on canvas with medals

81 x 102 cm

2023–2024

9.

Decorative Stump 2

GWASH Cast washing powder and glue, wood

25 x 80 cm

2003

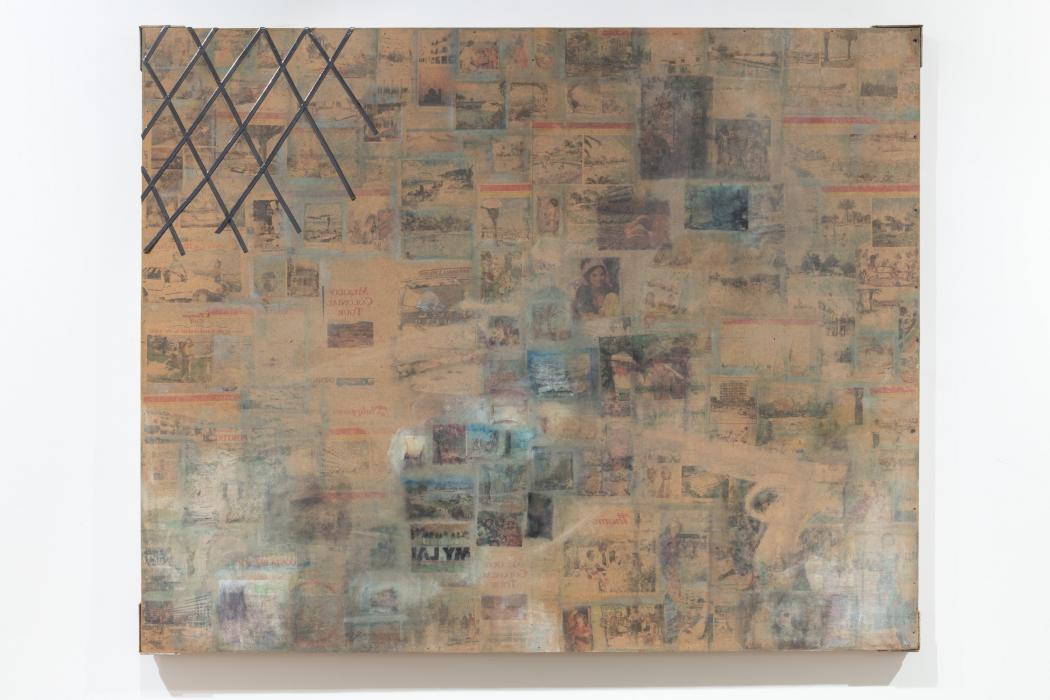

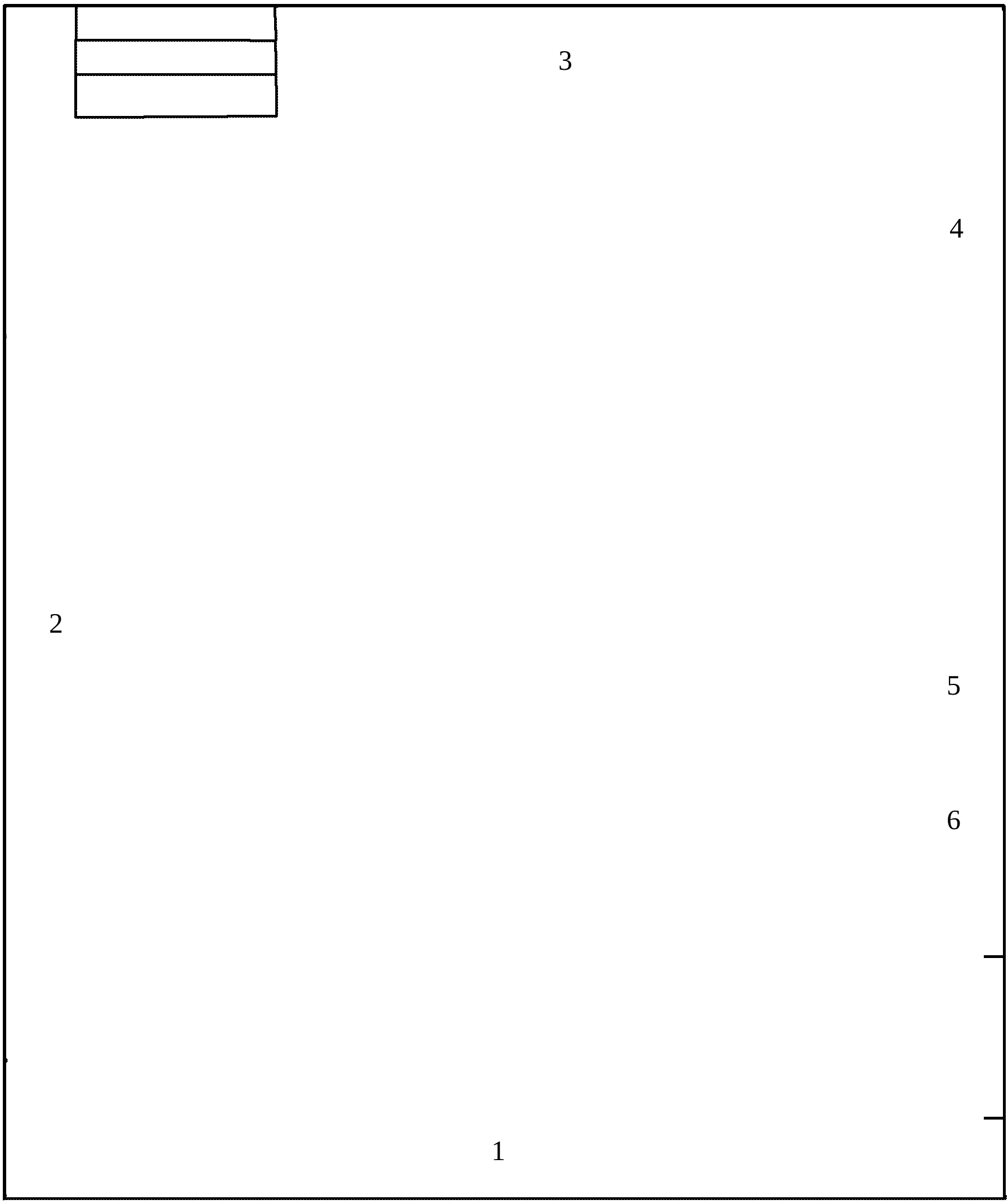

1.

Detour Patchwork

Collage on panel

121 x 153 cm

1987

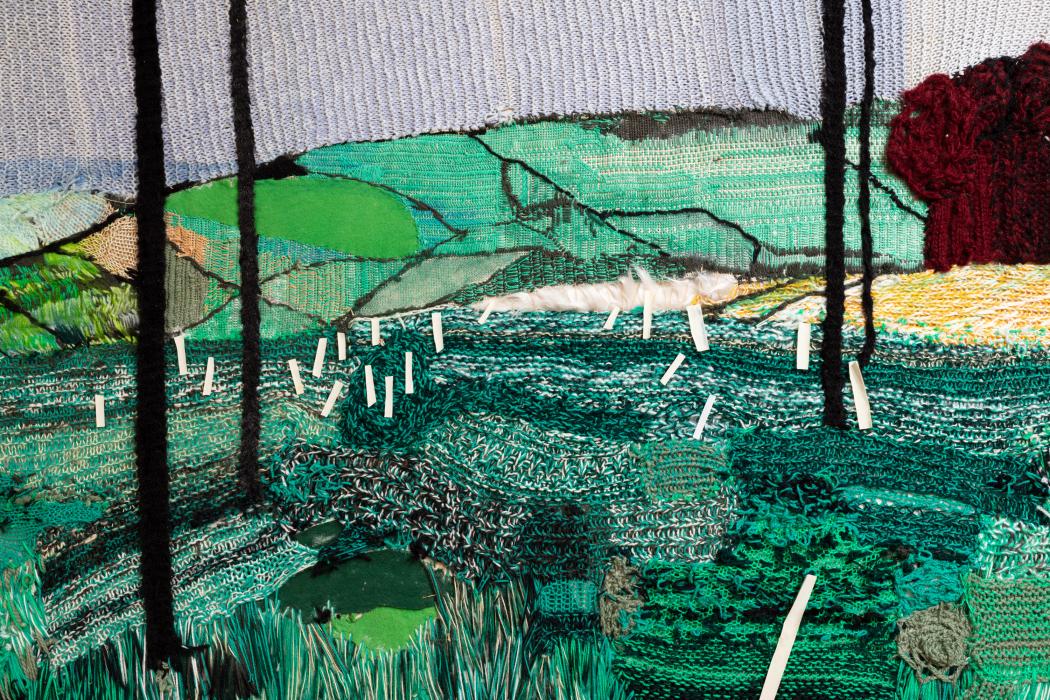

2.

Spending Time on an SAS Landscape

Knitting and sewing on canvas

139 x 173 cm

1986

3.

Laundered Air America Plane flies over Home Office Washing Line on its way to Libya. 1987

Oil paint on canvas with found clothing and washing line

153 x 214 cm

1986

4.

Repossession. Left on the Shelf

GWASH Cast washing powder and glue ornaments with an ornament fashioned from a lump of coal

12 x 180 cm

1991

5.

Bleach and Burn

Bleach and blowtorch on paper

37 x 58 cm

1985

6.

Coal Dust

Coal dust on paper

37 x 58 cm

1985

Susan Atkinson

Rose Cultivation

11.05.24 – 03.08.24

I find making art difficult – although I’ve always made it. I remember the feeling of excitement on my fifth birthday as I was given paints and brushes. My excitement soon turned to disappointment when my mother claimed I was making too much mess and so stopped me from painting. My sister often reminds me that as a child I drew on every available blank page of her story books; I remind her how our mother denied me drawing and painting materials. As a child I drew thousands of faces. Later, in the sixties, I did a three-year Diploma in Art and Design course in Visual Communications. When I resumed a practice in the late 1970s, having had children, the first drawings I made were of faces. By then I was beginning to understand that an art practice could be critical as well as celebratory. The seventies were a turbulent decade: a feminist movement was beginning to infiltrate mainstream culture and was seen as a threat to the shape of society organised according to a hierarchy of God, man and then woman as subordinate. Critical analysis of the male gaze was high on the feminist agenda.

On the 30th September 1967 pop music was brought out from the cold of the North Sea into the warm studios of the British Broadcasting Corporation: Radio One was born. I set my alarm for 7pm to hear Tony Blackburn introduce the first track, Flowers in The Rain by The Move. Harold Wilson’s Labour government had navigated Britain towards a more liberal society, one which had overseen the free availability of the birth control pill, which enabled women for the first time to control their fertility, abolition of the death penalty, and repeal of the law criminalising homosexuality. Comprehensive education, introduced in the mid-1960s, had, by the mid-1970s, phased out most of the grammar schools and the divisive eleven-plus exam. It could be argued that an attempt to level up the education system, together with the introduction of a pupil-centred style of teaching, led to a more confident and politicised youth – punk emerged.

People who identified as punk (rockers) were viewed by the establishment as a threat to political stability. Its powerful critique and rejection of accepted codes of conduct, dress and language spilled out onto the increasingly multicultural streets, offending and challenging some notion of respectability. The ridiculing of the national anthem by the Sex Pistols, the band with the highest profile at that time and the most profane, served to undermine the monarchy represented by The Queen. Elizabeth was the model of Britishness: the perfect English lady; the perfect English rose. By the late 1970s there was a general feeling of unrest. Youth was getting out of control; the establishment was unable to fully appropriate them and their music and shape them into a form which mainstream culture found palatable. They were viewed as leaning too much toward socialism – ‘reds under the bed’.

Blow Up Ad Man with gold medallion (acrylic on paper, 84x68cm, 1981) was made in response to the newly-elected Conservative government led by Margaret Thatcher. They had a clear political agenda to radically alter the economic base of the country from industrial production to commodity consumption. This image of a youngish man with a clean white t-shirt seemed to represent the shift from the dirt of industry to the illusion of the cleanliness of finance. In 1979 Saatchi & Saatchi produced a poster for the Conservative election campaign, depicting a long line of people with the slogan ‘Labour isn’t Working’. The slipperiness of the double entendre would be a vital instrument in their economic agenda. Around this time I noticed a tendency to use images of older women in adverts concerning money and investments (Good News for Investors, acrylic on paper, 74x59cm, 1980). The high-necked white blouse with the cameo brooch coveys a veneer of respectability and honesty.

I left art school in 1968. In my last year we were given an assignment to design some kind of advertising material; the subject matter was left open. I decided to advertise the Labour party. My design included hand-drawn faces of prominent male party members, including the then Prime Minister Harold Wilson. Subsequently I remember drawing Lyndon B. Johnson, then President of the United States, sitting at his desk playing with toy soldiers. The Vietnam war was raging and images of slaughter and bloodshed were beamed into people’s living rooms nightly through mainly black and white televisions. I also made a roulette wheel. The aim of this game was to spin (or revolve) the wheel and get it to stop at a point where names of leading figures of the student uprising in Paris in May 1968, such as Daniel-Cohn Bendit and Rudi Dutschke, or words such as ‘revolution’, could be made.

This line of thinking was not encouraged. Graphic design is a category of art that supports the economic and political system it is producing for. Questioning the political system therefore lay outside the remit of the category ‘graphic design’. I was soon channelled into what was then perceived to be the ‘right’ direction for a female. All the tutors were male. Politics had to be left behind. I did not learn about, for example, the Situationists until years later. I ended up making a life-size cardboard cutout of Queen Elizabeth I designed to stand outside some stately National Trust house, the Lord Mayor’s Christmas card and a pop-up book telling the story of Snow White. It was nearly ten years before I resumed any sort of practice and began to understand that the idea of freedom in the sixties was a superficial image.

A group of Welsh women for Life on Earth arrived at Greenham Common in September 1981 to protest against the Thatcher government’s decision to allow American cruise missiles to be stored at the Berkshire RAF base. The controversy around the Falklands War and the sinking of the Belgrano fuelled the peace movement: Thatcher was establishing herself as a strong Churchillian leader having defeated the Argentinians. Although Thatcher was a woman she continued to support and reinforce the status quo. She presented herself as feminine, not feminist, always with a handbag and freshly-set hair. She was filmed cutting roses in her expansive garden. It is a commonly held belief that a well-stocked arsenal and a nuclear capability is needed to defend a set of cultural values based on God, Queen and the nuclear family. In order to challenge the existence of nuclear weapons and an economy dependent on the production of arms, cultural values underpinning the justification for their existence also need to be challenged. Protest is a requirement by a country considering itself to be democratic. The peaceful march legitimises the idea that people are free to voice their opposition.

In 1968, 100 women gathered outside the Miss World pageant in Atlantic City, crowned a sheep and threw bras and beauty products into a freedom trash can. The Miss World pageant was held in the Royal Albert Hall, London, in November 1970. The event began with the bombing of a B.B.C. outside broadcast facility by The Angry Brigade. Although it failed it created a climate of fear; the audience were virtually penned in by barricades. The host Bob Hope opened the show with a stream of sexist remarks referring to the contestants as cows in a cattle market; a group of women had infiltrated the audience with the intention to disrupt replied to his mooing with booing. They threw flour bombs and rotten fruit; heckled and shook rattles. The apartheid regime in South Africa was already under pressure from a decade of protest and sent two contestants – one black and the other white. Grenada came first and black South Africa second. A lot of complaints were made about these rankings, which were most likely made to quell the increasing opposition to apartheid. A couple of years ago my granddaughter invited Sally Alexander, one of the main organisers of the 1970 Miss World protest, to speak at her university feminist group.

I protested at Greenham and made a series of paintings of my experiences. Garden at Greenham (acrylic on panel, 122x154cm, 1980) is a counter to the idealised English garden with manicured lawns promulgated by home and garden magazines. It is more like a Stone Age burial ground, untamed but ordered. The women cooked outside, they sometimes urinated in public. They were far from manicured. They were arrested and imprisoned and became experts in the law. Their behaviour transgressed the norms of society. At the same time that the women were cutting the periphery fence and entering the base Thatcher was cutting funding to education and the public services in a bid to privatise them. In 1985 I was briefly imprisoned for protesting in Leamington Spa against apartheid. I painted an image of a black South African woman behind a barbed wire fence on a shop front. Accompanying the image, painted text linked British nuclear weapons investment with uranium mining in South Africa. In prison I observed how craft was viewed as work, and all prisoners went to the Craft Room. The Art Room, however, was a zone of privilege. I made Spending Time on an SAS Landscape (knitting and sewing on canvas, 139x173cm, 1986), mainly knitted, after my release.

Thatcher was elected as Conservative Prime Minister in 1979. Her government was determined to alter the course of a post-world war two country that was socially minded and egalitarian, one which founded the NHS and funded state education. This vision of a new society was based on private as opposed to public ownership. It was based on finance capital as opposed to industrial capital – a system that could only benefit the few as opposed to the many. It could be argued that the Falklands war kept Thatcher in power as her strident manner and prompt assault on the funding of public services such as education was seemingly unnerving certain sections of society. The miners’ union led by Arthur Scargill was the most powerful closed shop union at the time and was responsible for bringing down the Heath government in 1972. Thatcher knew she had a fight on her hands (the miners did not forget their history: to prevent the miners from striking in 1926 Churchill was reported to have ordered machine guns to be placed on pitheads in South Wales and troops to be sent in to the Yorkshire coalfields). I joined striking miners on picket lines across the Midlands and Yorkshire; elsewhere, the peace movement continued its protests against the colonisation of American Cruise Missiles with a nuclear capability at Greenham Common and other military bases around the country. Some prominent women who lived at Greenham did not support any form of violence which made, for example, support for the miners difficult.

Coffee Table (mixed media, 103x125x35cm, 2003), a minimalist white metal box with glass lid, contains roses sculpted from washing powder and glue (a media that I invented from domestic materials to hand that I call ‘GWASH’), silk roses and a motif taken from the Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1503–15). A commemorative teapot with the images of George VI, The Queen Mother, Elizabeth (who would become Elizabeth II), and her sister Margaret Rose, is on the table. The text is a quote from the book Growing Roses by Peter McHoy. In the context of this work, the rose tends to be considered a symbol of Englishness, but the Chinese had been growing roses for thousands of years and these began to reach European growers in the late eighteenth century. Around 1781 a pink rose, R, Chinensis, now known as ‘Old Blush’, was planted in the Netherlands and soon came to England. Some years later a captain of the East India Company returned home with a red form of the same rose, which he had found growing in Calcutta and was named R, semperflorens, the ‘Bengal Rose’, or ‘Slater’s Crimson China’. Between them these two roses are responsible for the repeat flowering qualities in most modern roses. The rose, coffee and tea are products of empire. The British empire, like all European empires, was built on the colonization and exploitation of nations the British consider less developed and less cultivated than themselves. Roses, tea and coffee are commodities tied up with oppression and exploitation. Coffee Table was started in 2001 and finished during the second Iraq war. It is now understood that America and Britain invaded Iraq illegally.

Since the end of world war two, communism, underneath the surface and running like a rampant root, habitually popping up to undermine the seemingly progressive form of post-war cultural and economic expansion, has been framed as a threat. Propaganda surrounding socialism caused the term ‘socialism’ to really mean communism. Churchill hated communism and his attempt to hide his anti-Jewish sentiment was to divide the Jews into two opposing categories, promulgating the idea that there was a ‘good Jew’ and a ‘bad Jew’. The State of Israel was formed in 1948 after world war two. Its founder, David Ben-Gurion, was a Zionist and according to Churchill represented the former ‘good Jew’. Leon Trotsky and the Bolshevik Jews, responsible for the assassination of a corrupt monarchy leading to the formation of a communist political system, were characterised by Churchill as the latter – ‘bad Jews’. After the second world war, on the 5th March 1946, 24 days before I was born, Churchill gave a speech in Fulton Missouri where he used the metaphor of an ‘iron curtain’ descending from the Baltic to Trieste, dividing the world into those countries under the sphere of influence of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the United States of America.

In 1946 my father was in Palestine as part of a British army taskforce sent to help in the aftermath of the King David Hotel bombing in Jerusalem on 22nd July that year. The King David Hotel was headquarters of the British armed forces in Palestine – the nerve centre of British rule. The Irgun, a paramilitary Zionist organisation, was held responsible for killing 91 Arabs, Jews and British; 46 others were injured. Menachem Begin was the leader of the Irgun and subsequently became Prime Minister of Israel from 1977–1983. My father’s sympathy lay with the Palestinian Arabs. He described their treatment by the Zionist Jews, including the poisoning of their water wells, as an act of barbarity. His view of Begin was equally venomous.

The fruit bowl in Fruit Plate on Kit Bag (mixed media, 68x45cm, 1992) was made using GWASH and the kit bag was brought back from Palestine by my father in 1947. The kit bag was vital during world war two but is now obsolete. The fruit bowl could be considered purely decorative (the receptable of still life). However, against the background of the long-running Palestine-Israeli conflict, the kit bag, in the setting of a public space, becomes a vehicle for a discourse concerning the politics of this appalling conflict which began in the nineteenth century with the express purpose of eliminating the Palestinians from their land by a controlling Zionist regime. The Nakba happened in 1948 when Britain relinquished its mandate over Palestine. Although Palestine and Israel were partitioned, Israel was in the controlling position. An apartheid state emerged and those who had fled Palestine – their homeland – during this period were not, and still are not, allowed back.

Using GWASH I returned, once again, to consider the status of craft in relation to art with my line of (simulated China) plates commemorating heroines such as Rosa Luxembourg and Ethel Rosenberg (‘Commemorative Plates’ series, GWASH washing powder and glue with photocopies and photographs with The Allies commemorative plate, 20x220cm, 1992). The category of craft has traditionally been considered subordinate to art, often domestic and produced by women. These plates cannot be washed up or used and will bend and change shape, but not break; although bits of the decoration may fall off or chip when dropped. Creamware – refined earthenware – was created in Staffordshire around 1750. It was developed through experimentation and acted as a cheap substitute for Chinese porcelain – ideal for domestic use.

This work is a response to the idea that ornaments are politically neutral, their function seeming to enhance interior decor, based on personal taste. Ornament can indicate income bracket and level of education, and help create false stereotypes. I think my intended reading of these plates is to question a conditioned way of looking and judging what is good or bad: if they represent what is conventionally considered ‘good’ craft or ‘good’ art. In hindsight they were also made in response to the artistic trends of the 1990s, not big enough, sensational enough, or eye catching enough to capture the attention of a growing number of entrepreneurial investors, not least Eastern European oligarchs.

In my recent landscape paintings I am concerned with the way that the pastoral genre conceals processes of immiseration. In SAS Landscape: Made for the bedroom (acrylic on canvas, 51x22cm, 2011) I contrast the private domain of the domestic bedroom space with military territory. During the first Covid lockdown, when we became intimately acquainted with domestic spaces, I noticed an increase in visits to Edgehill – the first battle site of the English civil war in 1642. Most of the battle ground today belongs to the Ministry of Defence; the bodies of dead Roundhead and Royalist soldiers are buried there. The civil war marked the end of the divine right of kings and the rise of a larger wealthier middle class and the transition from feudalism to capitalism with the emergence of empire.

Back (bat) To the Future with Poppies on Edgehill (oil on canvas, 51x102cm, 2022) shows a bat with a bomb attached to it. This mad idea was thought up by the USA: the bomb consisted of a bomb-shaped casing with over a thousand compartments, each containing a hibernating Mexican free-tailed bat with a small incendiary bomb attached; the idea was that a plane carrying the bats would take off at dawn and then be released over the target area. It was hoped they would roost in trees and eaves of buildings until the timed devices were detonated. The bat bombs’ intended target was Japan. It was thought Japan’s style of architecture using paper and wood would ignite easily and start fires.

The most recent work presented at Josey is the oil painting Addicted to Poppies (oil on canvas with medals, 81x102cm, 2023–2024). This painting was made in response to a group of women I know, or knew, sitting waiting for a Slimming World class to begin; they were trying to put together poppies they had knitted from what looked like an official British Legion pattern. This was not an easy task. It was the same year the spectacle of thousands of ceramic poppies carpeted a huge area surrounding the Tower of London. The mainstream media, an instrument of the establishment I hardly need add, whipped up poppy frenzy, hence the plethora of crafted poppies.

The catalyst for the turmoil at the end of the 1960s was Vietnam – a war between communism and capitalism. Young American men were drafted and many tried to evade the call up. The lack of appetite to kill the communist enemy was viewed as a threat to democracy and protesters were labelled as ‘reds’, ‘Trotskyists’, ‘Maoists’, ‘commies’ – references to the Soviet Union and China, two powerful communist states. However, there appears to be a contradiction: China and Russia were and still are characterised by the West as restrictive and authoritarian. If protestors were challenging authority why would they align themselves with authoritarian regimes?

For a democratic society to function a confidence trick has to be performed on the bulk of its citizens. Information has to be suppressed and manipulated, school curricula dumbed down. Television, the medium which showed the world the visceral realities of war – the fear on the soldiers faces and the carpet bombing with Napalm – began to be more cautious and controlled. Tabloid newspapers tended to promulgate information expedient to the interests of the government of the time.

The relationship between celebrity and the poppy deepened. Strictly Come Dancing made the poppy into bling, decoration for entertainment – an Amazon search shows 1400 results for ‘bling poppy’. In Ireland the poppy remains an intensely politicised object. During Tony Blair’s terms of office he took the country to war on four occasions – Kosovo, Sierra Leone, Afghanistan and Iraq. His official portrait painted in 2008 features him wearing a remembrance poppy. Both the opium poppy and the corn poppy are political weapons. The meaning of peace has been changed from the idea that wars will end to the idea of continuous war necessary to keep peace at home. NATO and nuclear weapons will keep us safe. The poppy industry, both opium and corn, and the arms industry bloom in a climate of conflict. The invasion of Afghanistan breathed new life into opium making it into a powerful symbol of survival and resistance. The remembrance poppy as a symbol was invented by Moina Belle Michael, an American woman who was deeply affected by the poem ‘In Flanders Fields’ written by the Canadian John McCrae. Anna E. Guérin a French woman also took up the cause with Moina to export the idea of the remembrance poppy around the world. Ironically, the Cornflower is the preferred remembrance flower for the French.