Peter Cain, Alan Michael, John Miller, Kayode Ojo, Gili Tal

Image of the City

’It is clear that the form of a city or of a metropolis will not exhibit some gigantic, stratified order. It will be a complicated pattern, continuous and whole, yet intricate and mobile. It must be plastic to the perceptual habits of thousands of citizens, open-ended to changes of function and meaning, receptive to the formation of new imagery. It must invite its viewers to explore the world.’

Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City

‘Breton und Le Corbusier umfassen - das hieße den Geist des gegenwärtigen Frankreich wie einen Bogen spannen, aus dem die Erkenntnis den Augenblick mitten ins Herz trifft.’

Walter Benjamin, Das Passagen-Werk

Against the objectivist spirit of architectural functionalism and social positivism that under- wrote the great post-war experiments in urban development and renewal, Kevin Lynch’s now-classic study from 1960, from which this exhibition takes its title, sought to understand the city as a psychic phenomena. The key feature of the city was what he identified as its ”imageability”, a corollary of the characteristic visual markers (such as landmarks, paths, districts) that lend perceptual cognition a certain coherency and clarity in orienting itself; a measure of how successfully the composition of elements could be discerned and retained by consciousness, and thus reintegrated into the cognitive maps we construct of our lived environment. In contrast, a city with some paucity of these markers resulted in “low imag- eability”, in effect vitiating the subject’s capacity to situate themselves in relation to their environment, such that the affective sense of modern alienation emerges, at least in part, from a literal failure of spatial orientation.

As something like a mediary of sensible experience and conceptual understanding, neither purely subjective nor clearly objective in form, Lynch’s image of the city serves as the starting point for the exhibition. Yet what is valuable for our purposes is less his conclu- sions than the suggestive potential his approach yields once reoriented beyond the limits of urban theory. The late literary critic Fredric Jameson famously appropriated the notion of cognitive mapping as a speculative tool for plotting the ”situational representation on the part of the individual subject to that vaster and properly unrepresentable totality … of society’s structures as a whole”. Analogously, once refracted through the question of art and the aesthetic, the image of the city discloses its proximity to the visual imaginary of modernity as such.

For Walter Benjamin, the image of the city was undoubtedly a dialectical image, but a dialectics without resolution, a logic of estrangement. Unlike the notions of conquest and control that implicitly shore up the ideal type in Lynch’s schema, Benjamin’s vision of Paris - as ”the capital of the nineteenth century” - was spatially unnavigable and temporally out of joint. Ever the enemy of “the ideology of progress”, Benjamin saw that to achieve a political project for a future discontinuous with the present demanded the redemption of a forgotten past, an “awakening of a not-yet-conscious knowledge of what has been.” Surrealism had indicated the form under which the dream-work of capitalism might yield the emancipatory modernity latent within it; its content, the (unfinished) Arcades Project [Passagen-Werk], a refraction of the city at the juncture between the Paris of Balzac and the Paris of Hauss- mann, through the figure of the Baudelairean flâneur, whose aimless wander finds its formal counterpart in the cumulative textual fragments of the convolutes, if not the discontinuities of historicity itself.

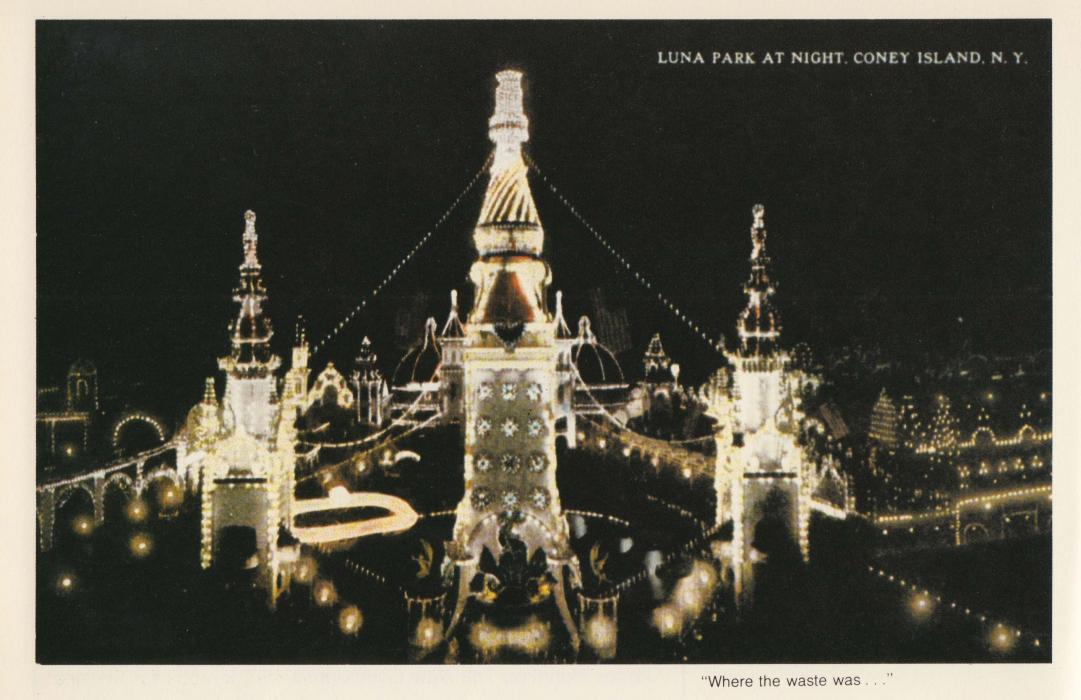

In his 1978 work Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto For Manhattan, Rem Koolhaas mapped a new kind of city, conceived under the sign of a new century and on the precipice of a new spirit of capitalism. For Koolhaas, the founding gesture of modern Manhattan can be found in the abstract Cartesian plan that, in 1811, carved up the island topology into 2,028 blocks; “The Grid”, Koolhaas reasons, “makes the history of archi- tecture and all previous lessons of urbanism irrelevant.” This was a practical exigency that, in this telling, doubles as an Oulipean constraint; in which the modernist link between Surrea- lism and Le Corbusier might be reconceived “retroactively” in New York’s foundation. The skyscraper internalises the logic of the grid, mapping the non-coincidence of utility and design onto the very division of inside and outside - an architectural break from Europe, Koolhaas claims bombastically, that “resolve(s) forever the conflict between form and function”. Thus the city’s programmatic utilitarianism becomes the unintended principle for an architectural vanguardism, a “mosaic of episodes” that “contest each other”, imper- vious to assimilation by any unifying perspective – an allegory, perhaps, for a particular moment in the self-image of American democracy itself, and undoubtedly a world away from the monolithic vision of boulevards, parks and facades that had disclosed an older moment of political modernity. Yet when Koolhaas first published his manifesto, New York was near bankruptcy and architecture was marooned between pastiche and commercialism; in hindsight, the west appeared on the brink of a new era of financialised capital that would revise the very concept of the city as the shared, collective site of the social.

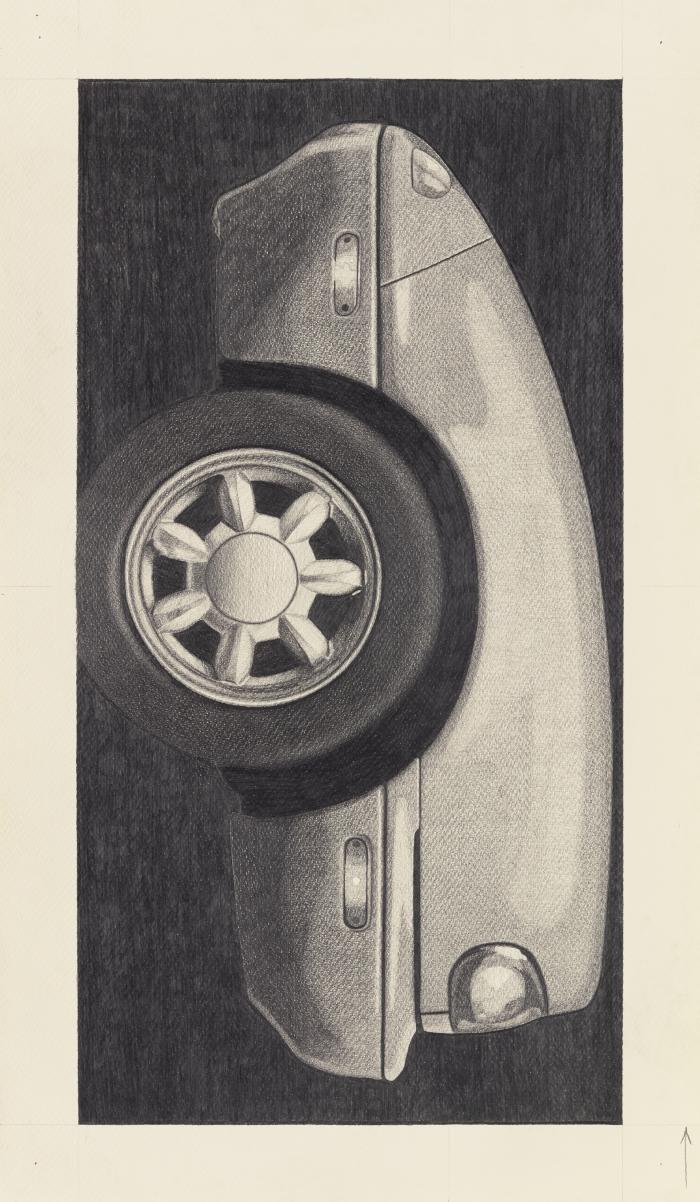

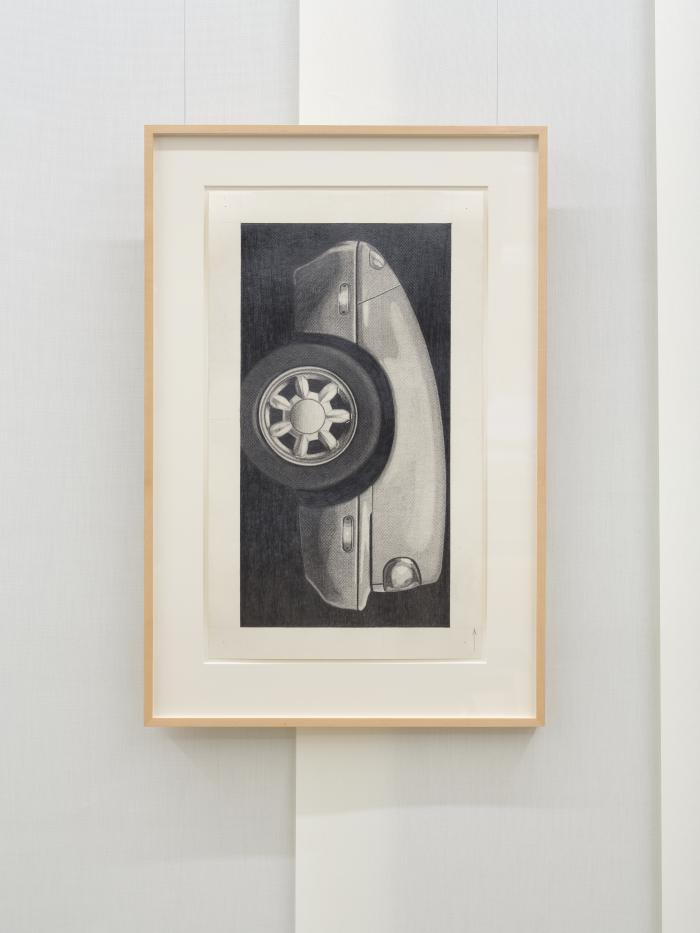

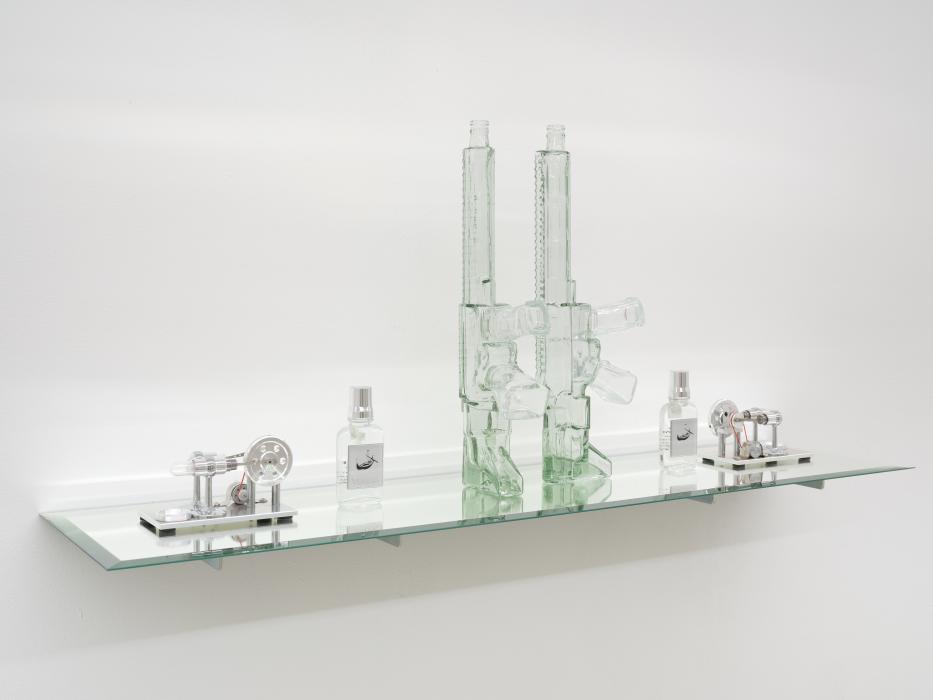

Today, the exhibition brings together artists whose works reevaluate this new conjuncture, amidst market prosperity and civic austerity, consumption, squander and mounting crises. If the present marks a certain distance from the “delirium”, provocation and formal rupture of previous epochs, capital itself proved to be singular in producing avant-garde affect, whether through the Verfremdungseffekt of market paroxysms or the violent severing of form from its content, the spatial from the temporal, just as digitality rends information from its physical body. Thus John Miller’s works, on the city and its crowds, disclose the labour in “leisure” and the artifice of our mediated self-image, the deceptive veil of the normative itself. If Peter Cain’s automobile paintings speak to a slightly earlier moment in the artifice of American iconography, as exercises in precise formal reduction they render unmistakable the hallucinatory fetish of visual commerce. The works of Alan Michael, by contrast, stage a verisimilitude of appropriation, employing a meticulous photorealism to explore questions of representation and the tensions between labour and virtuosity. Meanwhile, the spectrality of the value form is palpable in the work Kayode Ojo, who assembles totems of affluent cathexis into simulacral tableaux, haunted paeans to an other- worldly opulence. Finally, Gili Tal’s works meditate across varied motifs of the city, from the quotidian to the critical, exploring the loss of public space to private capture amongst the ideologies of the cosmopolis. Fractured and irresolute, the city persists in our shared aesthetic imaginary nonetheless, a fraught and crucial site of contestation for our fallen present, and the radical modernity yet to be unearthed.

Joe McCarney